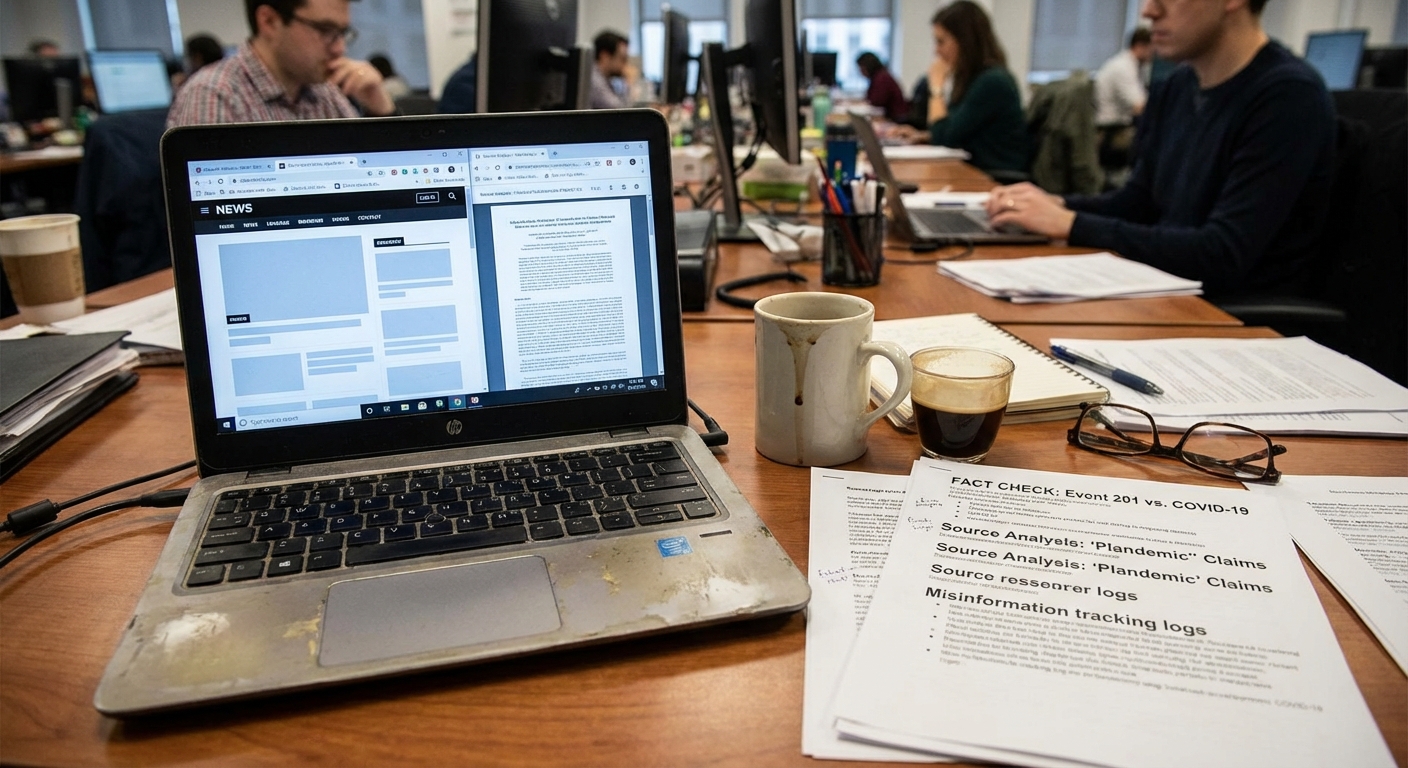

Intro: the items below summarize the most common pandemic planned event claims people cite. These are arguments offered by supporters of the claim, not proof the claim is true. We list the claim, where it comes from, and a practical test readers can use to evaluate it. The primary search phrase for this article is “pandemic planned event claims” and it appears here to help readers find the topic and sources quickly.

The strongest pandemic planned event claims people cite

-

Event 201 (October 18, 2019): claim — organizers “predicted” or rehearsed the exact COVID-19 pandemic; source type — tabletop exercise materials and press pages from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and partners; verification test — read the Event 201 scenario text and the organizer statement that the exercise was fictional and not a prediction. Johns Hopkins describes Event 201 as a fictional 3.5-hour tabletop exercise hosted with the World Economic Forum and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; organizers explicitly say it was not a prediction.

-

Simulation exercises (Clade X, Dark Winter, etc.): claim — tabletop or policy exercises show prior planning for a real pandemic; source type — published exercise scripts and academic writeups (Clade X report, Dark Winter script); verification test — compare the scripts’ stated purpose (training, preparedness) with claims that they predict or plan real events. Clade X and Dark Winter are documented simulation exercises designed to explore response gaps, not advance real-world operations.

-

Bill Gates and philanthropic involvement: claim — Gates (and partner organizations) helped plan or benefit from a planned pandemic; source type — lists of exercise partners, public statements, philanthropic grant pages; verification test — check partner lists for Event 201 and read Gates Foundation disclosures; also consult fact-checks about claims that Gates predicted or planned COVID-19. The Gates Foundation was a partner in Event 201 but organizers and fact-checkers emphasize the event was a preparedness exercise, not evidence of planning.

-

Film and media (e.g., Contagion): claim — popular films and media that depict pandemics are evidence of foreknowledge or “predictive programming”; source type — film production notes, interviews with filmmakers, expert commentary; verification test — check filmmakers’ research notes and expert explanations about coincidence, genre conventions, and prior outbreaks that informed scripts. Filmmakers and public-health commentators say Contagion was informed by existing science and past outbreaks and is not evidence of planning.

-

Patents and prior research: claim — patents or earlier publications show the virus or its features were known and therefore the pandemic was planned; source type — patent records, patent fact-checks; verification test — examine patent filings and independent analyses to determine which virus or technology the patent covers and whether it refers to SARS-CoV-2 specifically. Fact-checking shows patents cited by critics typically refer to earlier, related coronaviruses or vaccine/platform technologies and do not prove a planned release.

-

Gain-of-function funding and lab collaborations (EcoHealth Alliance, Wuhan Institute of Virology, NIH): claim — funded research created or enabled the pandemic; source type — grant documents, journal articles, congressional and NIH correspondence; verification test — read grant language, published experiment descriptions, and NIH reviews; note that experts and agencies disagree about whether specific funded work meets a narrow definition of “gain-of-function.” Government letters, journalism, and scientific reviews document the funding and the debate, but they do not by themselves prove the virus was intentionally released.

-

Intelligence or leaked documents: claim — classified or leaked intelligence shows intentionality; source type — news reports of intelligence assessments, leaked memos; verification test — evaluate the provenance and vetting of alleged intelligence and compare multiple reputable outlets; be explicit about conflicts among assessments. Some intelligence reports and later press stories have differed in assessment (for example, varying confidence levels about lab-leak vs zoonosis), which demonstrates disagreement among agencies rather than documented proof of planning.

How these arguments change when checked

When you trace each argument back to primary documents or authoritative reporting, several patterns recur:

- Many prominent examples (Event 201, Clade X, Dark Winter) are publicly documented preparedness exercises whose stated aims are training and identifying gaps — organizers and participants repeatedly say these were not predictions or plans for real-world operations.

- Fact-check organizations and mainstream news outlets examined and debunked or qualified widely shared social-media claims that these exercises “predicted” COVID-19; those fact-checks typically point readers back to the original exercise materials and organizer statements.

- Technical sources (patent records, grant abstracts, peer-reviewed papers) show a long history of coronavirus research, vaccines and platform technologies; taken alone, patents or prior research indicate prior scientific interest, not a coordinated plan to cause a pandemic. Accurate interpretation requires domain knowledge.

- Debate remains over the lab-leak hypothesis and the scope of some funded experiments. Investigations, inspector-general reports, intelligence assessments and peer-reviewed science have produced partially conflicting findings — those conflicts are real and important, and they do not equate to documentation that a pandemic was planned. Reported disagreements among agencies and analysts highlight uncertainty rather than settled proof.

Evidence score (and what it means)

Evidence score is not probability:

The score reflects how strong the documentation is, not how likely the claim is to be true.

- Evidence score (0–100): 22

- Why: primary documents (exercise descriptions, patents, grant abstracts) are available and show activities took place — this supports that exercises and research existed.

- Why: organizer statements and multiple fact-checks contradict the strongest interpretations (e.g., that Event 201 was a prediction), weakening the “planned” interpretation.

- Why: some relevant records (internal lab notes, classified intelligence) are incomplete or disputed in public reporting, leaving gaps that fuel speculation.

- Why: conflicts in intelligence and continuing debate about definitions (e.g., what counts as gain-of-function) mean documents do not converge to a single, well-supported claim of deliberate planning.

This article is for informational and analytical purposes and does not constitute legal, medical, investment, or purchasing advice.

FAQ

Q: What exactly are “pandemic planned event claims” and why do they spread?

A: “Pandemic planned event claims” assert that a pandemic was intentionally planned, rehearsed, or orchestrated by governments, corporations, or elites. They spread because documented activities (training exercises, film plots, patent filings, and legitimate research) are easy to reinterpret out of context, and because uncertainty and fear make causal narratives attractive. Reputable fact-checkers show that many individual elements are real but usually misinterpreted.

Q: Does Event 201 prove the pandemic was planned?

A: No — Event 201 was a documented tabletop exercise held on October 18, 2019, intended to explore preparedness challenges; the organizers explicitly stated it was fictional and not a prediction. Claims that it proves planning are inconsistent with primary materials and with multiple fact-checks.

Q: Could patents or prior research show foreknowledge of SARS-CoV-2?

A: Patents and prior research demonstrate pre-existing scientific work on coronaviruses and vaccine technology. Those records need careful technical reading: many patents cited by critics concern related viruses, detection methods, or platform technologies — not evidence of a coordinated plan to release a specific virus. Check patent documents directly and consult domain experts.

Q: If evidence conflicts about lab origins and funding, what should a careful reader do?

A: Treat conflicts as indicators of uncertainty. Read primary sources (grant abstracts, published methods, official correspondence) and reputable investigative reporting. Note when intelligence assessments differ in confidence and scope; conflicting conclusions among agencies indicate the need for more complete, transparent evidence rather than immediate acceptance of a sweeping claim.

Q: How can I test a specific “planned event” claim I encounter online?

A: Identify the original source (exercise text, patent number, grant page, news article). Read the primary document and look for explicit language about purpose (e.g., “scenario,” “fictional,” “training,” “model”). Then consult authoritative analyses or fact-checks that cite the same primary sources. If multiple reputable sources disagree, treat the claim as unresolved and seek further primary documentation. Examples and links used above illustrate that approach.

Beginner-guide writer who builds the site’s toolkit: how to fact-check, spot scams, and read sources.