The “Moon Landing Hoax” is a recurring claim that the Apollo Moon landings—especially Apollo 11—were staged or fabricated. This timeline focuses on key dates, public documents, and major turning points that shaped both the historical record of Apollo and the later growth of hoax narratives. It does not assume the claim is true; it maps what is documented, what is disputed, and what cannot be proven from public evidence alone.

This article is for informational and analytical purposes and does not constitute legal, medical, investment, or purchasing advice.

Timeline: key dates and turning points

-

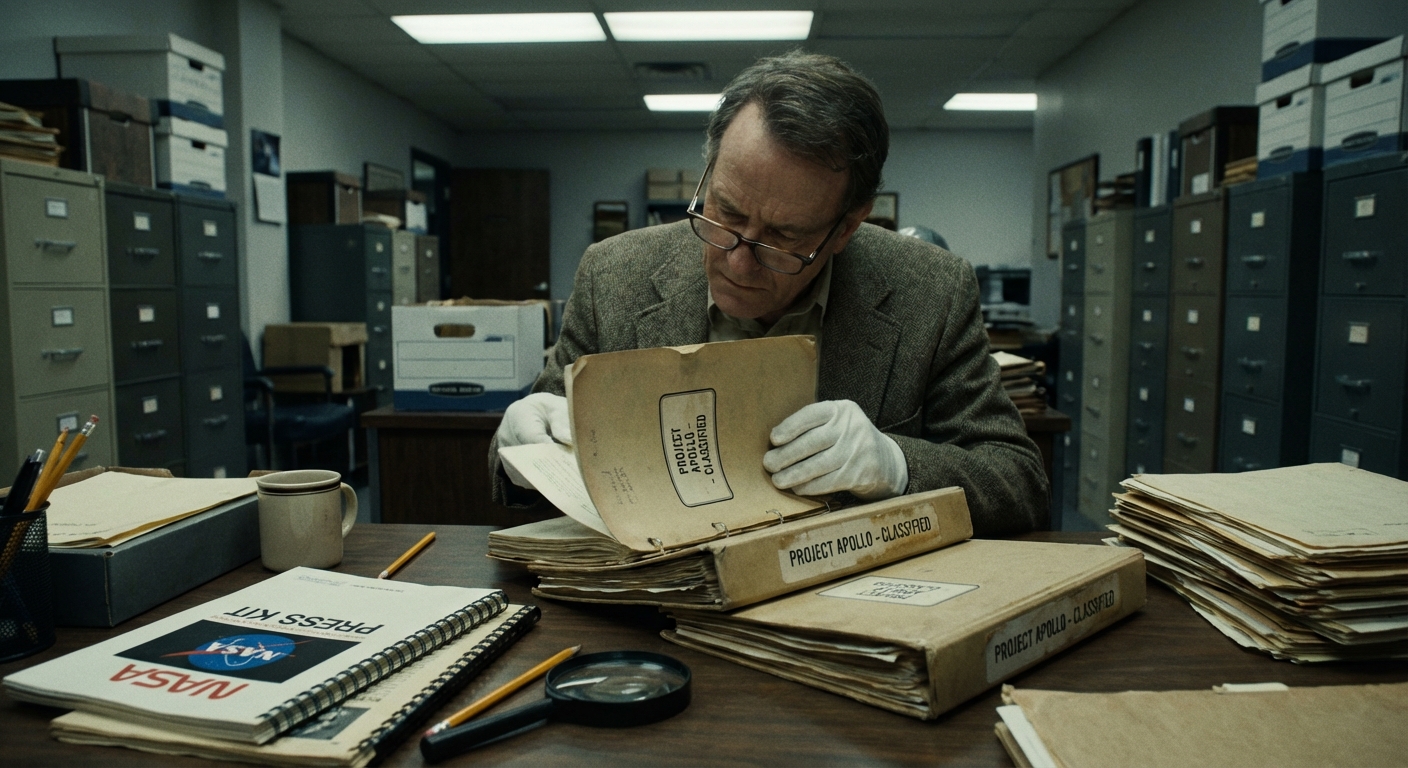

July 6, 1969 — Apollo 11 press materials published (NASA press kit). NASA’s Apollo 11 “lunar landing mission” press kit (preflight information) is a primary, contemporaneous document laying out mission plans and context. Source type: NASA archival PDF.

-

July 16, 1969 — Apollo 11 launches (mission overview). NASA’s Apollo 11 mission overview records the launch date and basic mission sequence. Source type: NASA history/mission overview.

-

July 20, 1969 — Landing and first EVA broadcast (mission summaries and transcripts). NASA’s Apollo 11 history page summarizes the landing time and the first steps broadcast; Library of Congress holdings preserve a “Mission Commentary, Transcript” artifact connected to the live coverage context. Source type: NASA mission history + Library of Congress/Capitol Visitor Center artifact entry.

-

July 24, 1969 — Splashdown and quarantine procedures (post-mission handling). NASA Earth Observatory describes recovery procedures including Biological Isolation Garments and quarantine logistics used after splashdown. This matters because hoax narratives sometimes treat quarantine as suspicious; the documentation shows it as a contamination-control protocol. Source type: NASA Earth Observatory explainer.

-

August 1969–1970s — Early technical archiving and publication ecosystem expands (transcripts and scientific documentation). USGS published an edited Apollo 11 voice transcript focused on geology (published 1974) drawing from mission audio tapes and NASA technical air-to-ground transcription, demonstrating how raw mission records were later curated for scientific use. Source type: USGS report record.

-

1976 — A key “hoax” milestone: Bill Kaysing’s self-published book. One of the earliest widely cited works associated with Moon-landing conspiracy narratives is Bill Kaysing’s We Never Went to the Moon (self-published, 1976). This is frequently described as an early catalyst for modern “Moon Landing Hoax” claims. Source type: secondary summary (not primary).

-

July 17, 2009 — LRO/LROC imagery begins highlighting Apollo hardware at landing sites. NASA’s photojournal entry “LROC’s First Look at the Apollo Landing Sites” describes orbital imaging that shows Apollo-era artifacts (e.g., Apollo 14 LM and ALSEP with astronaut tracks). These images become a common reference in later public debates about whether landings occurred. Source type: NASA photojournal.

-

July 19, 2009 — NASA Earth Observatory features Apollo 11 landing site imaging. NASA Earth Observatory explains that LRO captured imagery of the Apollo 11 descent stage and provides context about timing and resolution. Source type: NASA Earth Observatory “Image of the Day” explainer.

-

September 29, 2009 — “Second look” imagery of Apollo 11 site (orbital re-imaging). NASA’s “Apollo 11: Second Look” and the JPL Photojournal catalog entry document follow-up images of the Apollo 11 site under different lighting geometry. Source type: NASA photojournal + JPL Photojournal catalog.

-

2006–2020 (published 2023) — Modern high-precision lunar laser ranging continues. A 2023 paper on APOLLO (Apache Point Lunar Laser-ranging Operation) describes millimeter-accuracy lunar ranging data over many years. Lunar laser ranging is often discussed in relation to retroreflectors placed on the Moon, and it is used in physics and lunar-orbit analyses. Source type: research preprint.

-

Ongoing — NASA/JPL describes the Apollo 11 laser-ranging experiment’s scientific outputs. NASA JPL explains that Apollo-era lunar ranging has produced measurements used for lunar orbital/rotation knowledge, relativity tests, and Earth-Moon dynamics (e.g., recession rate). This is frequently cited as continuing, instrument-based evidence connected to Apollo surface deployments. Source type: NASA JPL article.

-

April 23, 2025 (metadata update) — NASA Open Data portal highlights a “Lunar Sample Atlas” dataset. NASA’s open-data listing describes an atlas of Apollo samples photographed and documented in the Lunar Sample Laboratory, with metadata indicating recent update activity. Discussions about lunar samples are a major flashpoint in Moon-hoax debates; this dataset represents a public-facing documentation node, though it is not, by itself, a chain-of-custody proof. Source type: NASA Open Data dataset listing.

Where the timeline gets disputed

1) “Documented mission record” vs “fabrication hypothesis.” NASA mission summaries and archival documents (press kits, mission overviews, and later curated transcripts) document Apollo 11’s timeline and operations, but hoax proponents may argue documents can be falsified. From an evidence perspective, the dispute often turns on whether independent, non-NASA lines of evidence exist and whether they converge.

2) Orbiter images: what they show, and what skeptics argue. LRO/LROC images are frequently presented as showing hardware and tracks at Apollo sites (a strong visual, physical-artefact claim). Skeptics sometimes argue imaging can be manipulated. The key analytical point is that these images come from a spacecraft mission with broad scientific goals and extensive public releases, not a one-off “proof” product; however, resolving manipulation claims ultimately requires trust in the imaging pipeline and independent verification. NASA’s photojournal entries and Earth Observatory explain the images and context, but do not function as a courtroom-style forensic audit.

3) Laser ranging and retroreflectors: strong physics, but not always understood by audiences. NASA JPL describes lunar laser ranging results and uses, and NASA Photojournal entries discuss retroreflector imaging (e.g., Apollo 15’s reflector as a “primary target”). Supporters treat this as strong instrument-based evidence tied to surface deployments; skeptics sometimes shift the claim to alternative explanations (e.g., reflectors could have been placed by uncrewed missions). The timeline takeaway: laser-ranging evidence is often central in debates, but interpreting “what it proves” depends on the specific claim being made and which deployments are in scope.

4) Popular media turning points can amplify hoax narratives. While not “evidence,” media events matter in the spread of the claim. For example, reporting around television debunking/entertainment content notes that Fox aired a “Did We Land on the Moon?” program in 2001, which some commentators describe as a cultural accelerant for the hoax narrative’s mainstream visibility. (This is about influence, not proof.)

Evidence score (and what it means)

Evidence score: 82/100

-

High availability of primary documentation (NASA mission overviews and contemporaneous press materials) supports reconstructing what was claimed to happen and when.

-

Independent institutional records exist (e.g., USGS publication derived from mission audio/transcripts; Library of Congress/Capitol artifacts referencing mission transcripts), strengthening the documentary trail beyond a single webpage.

-

Instrument-based and repeatable measurement lines (lunar laser ranging described by NASA JPL; modern high-precision ranging programs published in research literature) provide continuing, testable outputs relevant to surface deployments.

-

Orbital imaging adds a physical-artefact layer (LRO/LROC releases) that is difficult to reconcile with some versions of a total hoax claim, though it still depends on trust in spacecraft imaging and data handling.

-

Score is not 100 because many “hoax” arguments are unfalsifiable at the level of absolute certainty (a determined skeptic can always assert fabrication), and because some public-facing pages are summaries rather than full forensic disclosures.

Evidence score is not probability:

The score reflects how strong the documentation is, not how likely the claim is to be true.

FAQ

What is the “Moon Landing Hoax” claim, in plain terms?

The Moon Landing Hoax claim alleges that Apollo lunar landings—most commonly Apollo 11 in July 1969—were staged and presented as real. This article does not endorse that claim; it tracks the documentary and public turning points that shape the dispute.

What primary documents exist for Apollo 11 (and why do they matter in Moon Landing Hoax debates)?

Primary documents include NASA’s Apollo 11 press kit (published July 6, 1969) and mission overview materials detailing dates and mission milestones. These help establish what was officially stated at the time and how the mission was described operationally.

Do lunar orbiter photos address Moon Landing Hoax claims?

LRO/LROC imaging releases are commonly cited because they describe images of Apollo landing sites and artifacts. They are strong “physical site” evidence in public debate, though critics may dispute authenticity or interpretability without independent pipeline audits.

How does lunar laser ranging relate to Moon Landing Hoax claims?

NASA JPL describes how laser ranging to the Moon yields scientific results (Earth-Moon dynamics, relativity tests, lunar rotation/orbit refinements). Because retroreflectors were placed during Apollo missions, this is often discussed as continuing, measurable evidence connected to Apollo surface activity.

When did modern Moon Landing Hoax narratives become widely visible?

One commonly cited early catalyst is Bill Kaysing’s 1976 self-published book. Later, mass-media events (including early-2000s television programming and subsequent debunking coverage) helped keep the claim in circulation and introduce it to new audiences.

Science explainer who tackles space, engineering, and ‘physics says no’ claims calmly.