Intro: The following are the strongest arguments people cite when asserting the Polybius arcade game legend — presented as arguments, not proof. Each entry notes the type of source the argument depends on and a practical verification test. This article treats the story as a claim and keeps neutral, analytical language while citing the public records, journalism, and research that have shaped the discussion.

The strongest arguments people cite

- Argument: An early online entry (hosted on coinop.org) describes Polybius, claims a 1981 date and a screenshot/ROM fragment — supporters treat that entry as a primary lead. Source type: fan/archival website entry. Verification test: Inspect Wayback Machine archives, server timestamps, and any claimed ROM or screenshot metadata; seek independent archival copies or contemporaneous references (newspapers, trade magazines, arcade catalogs) from 1981.

Why it matters: The coinop.org entry is the earliest known web-era locus for the story and therefore underpins later retellings. Researchers who have followed the record note that the coinop entry is the pivot point for later coverage.

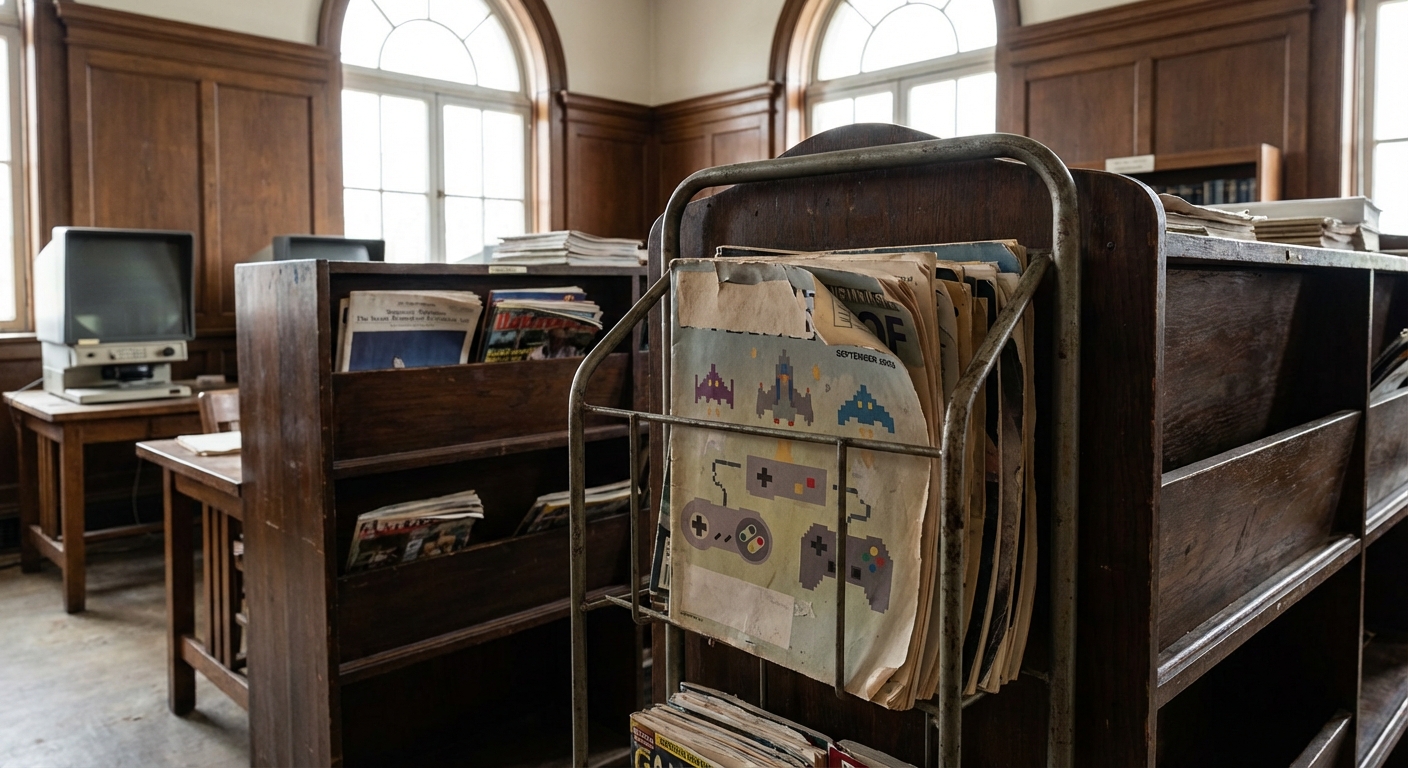

- Argument: GamePro magazine published a 2003 feature (“Secrets & Lies”) that introduced Polybius to a mass audience and treated the evidence as ‘‘inconclusive’’ — supporters say mainstream coverage validates the claim’s plausibility. Source type: magazine feature. Verification test: Locate the September 2003 GamePro article (original or archived copy), read the reporter’s sourcing, and compare what GamePro actually concluded versus how supporters quote it.

Why it matters: The GamePro piece amplified the story beyond hobbyist forums; tracking what that article actually said is central to assessing how much of the legend stems from later publicity.

- Argument: Eyewitness-style posts and later personal claims (for example, people posting under handles who say they worked on or saw Polybius) — supporters cite those testimonials as direct evidence. Source type: forum/newsgroup posts, anonymous first-person accounts. Verification test: Cross-check names/handles against employment records, contemporaneous local news, and independent corroboration; treat anonymous posts as low-verifiability until supported by documentary evidence.

Why it matters: Many later retellings rely on collectible anecdotes or claimed former developers; historians of the legend emphasize that these claims typically lack verifiable documentary support.

- Argument: Connections between the legend and real 1980s occurrences (police raids on arcades, documented player illnesses, and documented experiments on media or biofeedback) — supporters treat these as plausible real-world anchors for the claim. Source type: contemporaneous news reports and declassified research (e.g., arcade incidents, medical case reports, MK-Ultra historical records). Verification test: Locate the original 1980s newspaper articles, police records, or medical case documentation and verify whether any account mentions a game named Polybius or an unbranded cabinet matching the legend.

Why it matters: Several researchers say the legend likely stitched together unrelated 1980s events (such as documented seizures at arcades and law-enforcement activity) — identifying which events actually occurred and what they said is essential to separating fact from inference.

- Argument: Later investigative projects (notably a long-form YouTube documentary and subsequent deep-dive articles) conclude the story most likely started online in the late 1990s/early 2000s — supporters sometimes interpret this as evidence of a deliberate hoax or viral stunt. Source type: investigative documentary/long-form journalism (example: the Ahoy documentary and multiple retrospective articles). Verification test: Review these investigations for their methods (archival searches, interviews, Wayback Machine checks); verify their citations back to primary sources like coinop.org and archived newsgroups.

Why it matters: Scholarly and journalistic investigations that trace the provenance of the legend to late online postings are the strongest counter-claims to the story’s 1981 historicity; they show how the narrative spread and where it likely originated.

How these arguments change when checked

When the strongest arguments are tested against primary documents and archives, a pattern emerges: the coinop.org entry (and its claimed screenshot/ROM fragments) is the pivot for later claims, but independent contemporaneous evidence from 1981 (trade press, local newspapers, arcade industry lists, or factory/manufacturer records) is absent. Major retrospective investigations conclude that the story’s documented trail begins in the internet era rather than the early 1980s, which weakens claims that a secret, widely harmful cabinet circulated in arcades in 1981. However, some of the real 1980s events frequently cited as context (police raids, player medical incidents, and government interest in media experiments) are documented and can explain why the legend feels plausible.

This does not mean every detail supporters give is proven false — it means the documentary support for the central claim (that a game named Polybius was released in 1981 and caused the harms described) is weak or absent. Investigations that attempt to validate named people or ROM images consistently find either unverified claims or materials created later to match the legend.

Evidence score (and what it means)

- Evidence score: 15 / 100.

- Score drivers:

- Earliest documented references appear in the web era (coinop.org and later mass-market pieces), not in contemporaneous 1980s sources.

- No verified physical Polybius cabinet, ROM dump, or production/manufacturer records have been produced.

- Multiple thorough retrospective investigations (journalistic and hobbyist) trace the story’s spread to late internet postings and show inconsistent eyewitness accounts.

- Real 1980s events cited as context (seizures at arcades, police raids, government experiments) are documented, but none establishes the existence of a Polybius product matching the claim.

Evidence score is not probability:

The score reflects how strong the documentation is, not how likely the claim is to be true.

This article is for informational and analytical purposes and does not constitute legal, medical, investment, or purchasing advice.

FAQ

Q: Is there a verified Polybius ROM or cabinet that proves the claim?

No verified ROM image, circuit board dump, or authentic cabinet photograph that dates from the early 1980s has been produced for public scrutiny. Multiple researchers and journalists report that claimed ROMs and cabinets surfaced later and could not be independently authenticated.

Q: Did reputable investigators conclude Polybius is a hoax?

Investigators who traced the documentary trail (including web-era research and long-form retrospectives) have concluded that the legend’s verifiable records begin online rather than in 1981, and many describe the story as an urban legend or an internet-era creation. These investigators typically cite the lack of contemporaneous evidence and the primacy of coinop.org as decisive factors.

Q: Why do people still believe the story despite weak documentation?

Because the legend borrows believable elements from real events (arcade seizures, police actions, government experiments) and uses vivid imagery (men in black, addictive cabinets), it has strong memetic appeal; once repeated in magazines, videos, and forums, anecdotal details accumulate and feel convincing even without primary proof.

Q: What would change the assessment?

Discovery of contemporaneous, verifiable primary sources — a dated production record, a verifiable 1981 ROM image with provenance traceable to a manufacturer or arcade operator, or a contemporaneous newspaper/trade-magazine report naming Polybius — would materially raise the evidence score. Conversely, authenticated evidence showing the coinop entry was a later fabrication would further lower the score.

Myths-vs-facts writer who focuses on psychology, cognitive biases, and why stories spread.