The “Paul Is Dead” claim alleges that Paul McCartney died in the 1960s and was secretly replaced by a look‑alike, with the surviving Beatles leaving “clues” in songs and album artwork. This article treats that account strictly as a claim: it summarizes what proponents assert, documents the record of how the story rose and spread in 1969, and separates confirmed facts from inferences and fabrications.

What the Paul is dead claim says

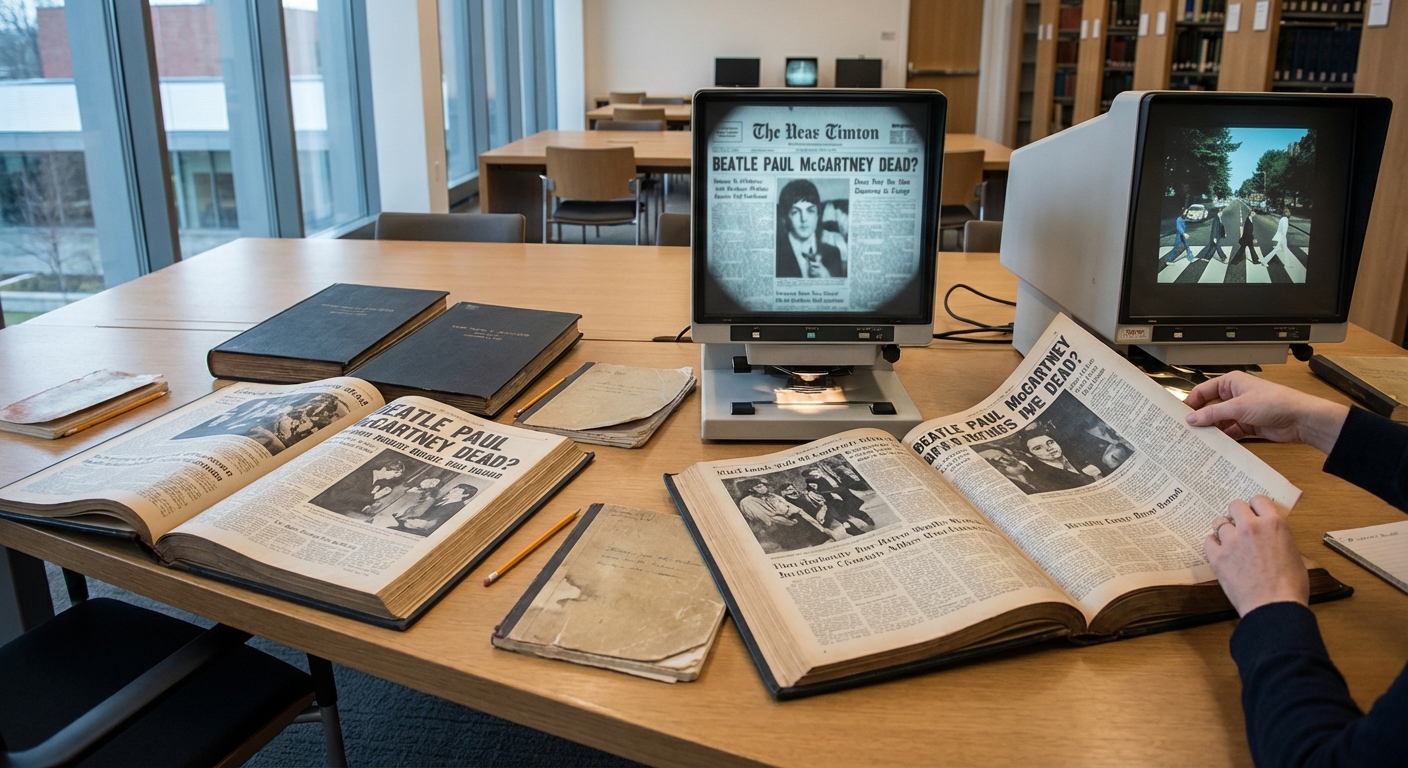

Proponents of the “Paul Is Dead” claim typically assert three linked ideas: (1) Paul McCartney died (usually placed in 1966) or was fatally injured; (2) the Beatles and others arranged a cover‑up and replaced him with a look‑alike; and (3) the group signalled the truth through covert “clues” hidden in song lyrics, backward tapes and album photography (most famously clues alleged on Sgt. Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour, the White Album and the Abbey Road sleeve). These themes are central to the claim as circulated in 1969 and later retellings.

Where it came from and why it spread

Multiple documented events explain how the claim went from local rumor to international phenomenon in October–November 1969. A short summary of the most widely reported turn of events is below; independent sources agree on the broad sequence even when details differ.

- September 1969 — campus rumors and early press: Student newspapers and campus conversations recorded circulating hints about McCartney’s health and oddities on album sleeves; one widely cited early published item is a September piece in the Drake University student paper that asked, “Is Beatle Paul McCartney Dead?” which helped seed later attention.

- October 12, 1969 — Detroit radio amplification: A caller to Detroit FM station WKNR discussed backward messages and other alleged clues; host Russ Gibb and callers spent airtime examining them. That broadcast is widely credited with amplifying the story and encouraging listeners to hunt for more “evidence.”

- October 14, 1969 — Michigan Daily satire becomes a source: University of Michigan writer Fred LaBour published a knowingly satirical item in The Michigan Daily titled “McCartney Dead; New Evidence Brought to Light,” inventing several of the more baroque clues (including the fictional replacement name William Campbell). Despite its satirical intent, the piece was picked up and circulated as if factual, dramatically widening the rumor’s reach.

- Mid–late October 1969 — radio specials, press coverage and denials: WKNR produced follow‑up programming (including a two‑hour special), other DJs and stations repeated and expanded the theory, and mainstream outlets (and the Beatles’ press office) issued denials; John Lennon and other Beatles spoke dismissively of the story on radio and in interviews.

- November 1969 — Life magazine interview: Life located McCartney at his farm and published an interview and photographs that many historians credit with reducing the rumor’s momentum. The Life cover story explicitly presented the case that Paul was still alive and included McCartney’s direct rejection of the claims.

What is documented vs what is inferred

Documented (verified by contemporaneous sources): the emergence of campus newspaper items in September 1969; the WKNR call and on‑air discussion on October 12; the Michigan Daily satire by Fred LaBour on October 14; radio specials such as WKNR’s “The Beatle Plot” (October 19); Beatles press office denials and interviews given by John Lennon and others; and Life magazine’s November 1969 interview and photo session with Paul McCartney. These events are recorded in multiple independent outlets and later historical summaries.

Plausible but unproven inferences (often promoted by supporters): that a death actually occurred in the mid‑1960s; that the Beatles or MI5 orchestrated a secret replacement; and that specific song snippets or photographic details were intentionally planted as a coordinated message about Paul’s death. The historical record documents the existence of alleged “clues” and that people interpreted them that way, but it does not provide corroborating primary evidence for an actual death or official cover‑up. Many of the most specific “clues” (names, dates, precise backwards messages) were fabricated, misheard, or invented in satirical sources.

Contradicted or refuted elements: direct rebuttals include on‑the‑record denials from the Beatles’ press office and interviews in which McCartney and Lennon called the story false or absurd. Life’s November 1969 interview and photos of McCartney were explicitly presented to counter the rumor; contemporaneous news outlets also reported the story as a hoax once the satirical origin and radio amplification became clear. These rebuttals are documented in press records from October–November 1969.

Common misunderstandings

- Backward masking as proof: Claims that playing tracks backward yields explicit, intentional messages are usually the result of pareidolia (hearing meaningful phrases in ambiguous audio) or selective editing; documented contemporary reports show many claimed backward messages were suggested and repeated by listeners rather than demonstrated as intentional production choices.

- All clues originate with the Beatles: some alleged clues were invented in satire or by radio callers and then retrofitted to earlier releases. The most elaborate narrative elements (replacement name William Campbell, precise accident accounts) trace to satirical or invented sources rather than band statements.

- Media coverage equals verification: intense press attention in October 1969 documented the rumor’s spread but is not evidence that the underlying claim is true; contemporaneous reporting also includes denials and corrective pieces.

This article is for informational and analytical purposes and does not constitute legal, medical, investment, or purchasing advice.

Evidence score (and what it means)

Evidence score: 10 / 100

- Score driver — Strong documentation that a rumor circulated widely in October–November 1969 (radio logs, student newspapers, mainstream press).

- Score driver — Primary sources (Michigan Daily satire, radio program recordings/transcripts, Life interview/photos) document how the story formed and declined, increasing confidence in the provenance of the rumor.

- Score driver — Very weak or no primary evidence supporting the core factual claim that McCartney died and was replaced; best sources directly contradict or fail to support that assertion.

- Score driver — Many specific “clues” trace to invented, satirical or misheard origins, reducing the evidentiary value of those items.

Evidence score is not probability:

The score reflects how strong the documentation is, not how likely the claim is to be true.

What we still don’t know

- Whether any earlier, less well‑documented British rumors predate the U.S. campus wave in ways that materially change the origin story; sources indicate rumors existed in 1966–67 but details are sparse and sometimes contradictory.

- Exactly which individual(s) first compiled the set of alleged “clues” that became canonical; several callers, students and DJs contributed, and later retellings compressed those contributions. Contemporary sources identify multiple contributors but disagree on primacy.

- How much commercial incentives (e.g., increased record sales) versus genuine belief among fans drove the continued circulation of the claim after official denials — there is documentation of a sales bump but not a full causal breakdown.

FAQ

What is the “Paul is dead” Beatles claim?

The “Paul is dead” Beatles claim asserts that Paul McCartney died in the 1960s and was secretly replaced, with the Beatles embedding clues in records and artwork to reveal the truth. The historical record documents when and how that claim spread (radio calls, a satirical Michigan Daily piece, and national coverage) but provides no primary evidence that McCartney died or was replaced.

Who started the story?

Scholarly and journalistic reconstructions point to a mix of campus rumors (including a Drake University student paper item), a prominent radio call to Detroit’s WKNR on October 12, 1969, and a satirical Michigan Daily article by Fred LaBour on October 14, 1969. The Michigan Daily satire and follow‑up radio specials were pivotal in turning localized rumors into a widespread phenomenon.

Did the Beatles ever admit anything?

No credible contemporaneous evidence shows the Beatles admitting that Paul died or was replaced. The band’s press office and members issued denials; John Lennon and Paul McCartney publicly dismissed the story, and Life magazine’s November 1969 interview with McCartney presented photographic and on‑the‑record rebuttal material.

Why did the rumor spread so quickly?

The rapid spread is documented and attributable to a combination of factors: free‑form radio discussion that encouraged clue‑hunting, campus media and satire that read as plausible to some readers, the cultural climate of skepticism about institutions in 1969, and sensational reporting that amplified the narrative before clarifying corrections arrived. The case is often cited in communications studies as an early example of viral rumor dynamics.

Where can I find primary sources from 1969?

Primary contemporaneous materials include WKNR radio program logs/recordings, the October 14, 1969 Michigan Daily issue by Fred LaBour, press office statements and news coverage in October–November 1969, and Life magazine’s November 7, 1969 interview/feature on McCartney. Archival newspaper collections and university libraries are typical places to access these items.

Culture writer: pop-culture conspiracies, internet lore, and how communities form around claims.