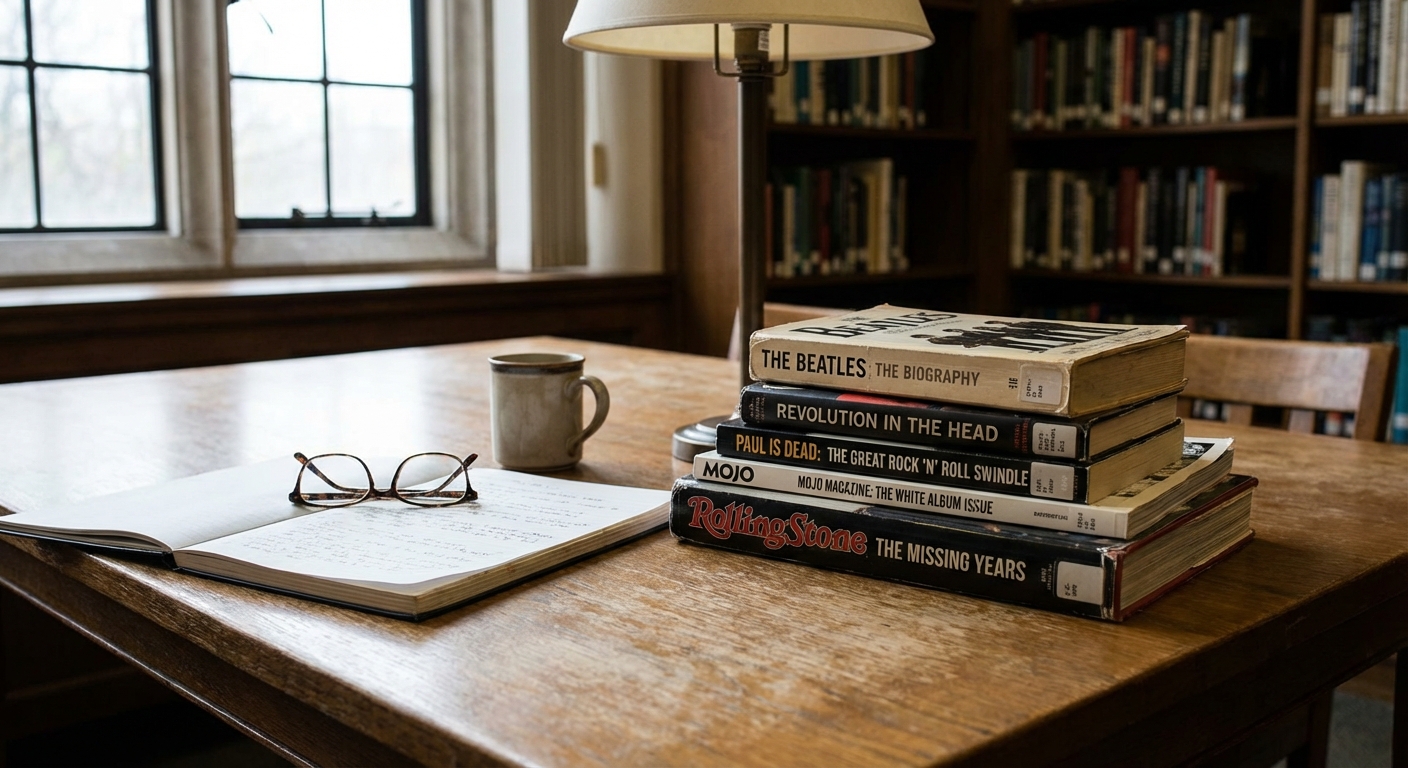

Intro: The items below list the arguments supporters of the ‘Paul Is Dead’ (The Beatles) claim most often cite. These are presented as claims and evidence that proponents point to, not as proven facts. Where possible, each argument shows its provenance and a simple test or source check a reader could use to evaluate it.

The strongest arguments people cite

-

Abbey Road cover as a funeral procession — source type: album artwork interpretation; verification test: compare the walk order and props on the cover to the suggested symbolism.

Why people cite it: On the Abbey Road sleeve, John, Ringo, Paul (barefoot and out of step), and George appear walking across a zebra crossing; believers read this as a symbolic funeral procession (e.g., preacher, undertaker, corpse, gravedigger). Contemporary and later commentaries document that fans interpreted the photo this way and that the image played a central role in the 1969 clue-hunting craze.

-

License plate “28IF” on a parked Volkswagen Beetle — source type: photographic detail; verification test: inspect high-resolution Abbey Road photos and production notes to see what the plate actually reads and relevant dates for Paul’s age.

Why people cite it: The plate is read as “28 IF” → “28 if (Paul had lived),” implying he would be 28 had he not died. Investigations show the plate reads as photographed and that proponents applied symbolic numerology (and inconsistent age math) to the image; critics note Paul would have been 27 at Abbey Road’s release and that the plate reading is plausibly coincidental. Documented analyses and cataloguing of the Abbey Road photo support that the license-plate detail was one among many ambiguous elements fans seized on.

-

Backmasked or reversed audio snippets — source type: alleged hidden audio when records are played backwards; verification test: listen to original recordings, consult published transcripts and expert audio analyses.

Why people cite it: Callers and DJs in 1969 claimed that parts of songs such as “Revolution 9” (a repeated “number nine” phrase) sounded like “turn me on, dead man” when reversed, and that other passages contained phrases like “I buried Paul” when spun backwards. These claims were central to early radio discussions that amplified the rumor. Later examinations show many of these backward-interpretations rely on suggestion and pareidolia; reputable histories of the episode document the role of reverse-play claims in spreading the idea.

-

Lyrics allegedly referencing a death or replacement (examples: perceived lines in “Strawberry Fields Forever” and elsewhere) — source type: lyric interpretation; verification test: check original studio takes, published lyrics, and contemporaneous statements from the Beatles or producers.

Why people cite it: Lines taken out of context or misheard phrases (for example, a phrase interpreted as “I buried Paul”) have been treated as intentional clues by believers. Scholarly and journalistic studies emphasize that many cited lyrics are ambiguous, edited, or misheard and that the Beatles themselves denied encoding such a conspiracy.

-

Physical differences and handedness — source type: photo comparisons and anecdote; verification test: examine dated photographs, film, and trustworthy biometric or forensic commentary where available.

Why people cite it: Some proponents point to purported differences in facial features, fingerprints, or the handedness shown in photos (Paul appearing to hold a cigarette in his right hand on Abbey Road, while he is left-handed) as evidence of a replacement. Later interviews and retrospective analyses show that the Beatles’ informal photos, camera angles, handedness in candid shots, and wardrobe choices can explain many of those apparent discrepancies; at least one researcher noted that some photographic comparisons were selective or measured improperly.

-

Campus press satire and radio amplification (Fred LaBour / WKNR programs) — source type: contemporary journalism and radio broadcasts; verification test: locate the 1969 Michigan Daily parody and radio logs or transcripts from October 1969.

Why people cite it: The modern spread is traceable to a caller and a Detroit-area DJ (Russ Gibb) who discussed the rumor on air on October 12, 1969, and to a satiric Michigan Daily column by Fred LaBour that catalogued “clues” (LaBour later said he invented many of them). Primary reporting and later retrospectives identify these moments as accelerants in the rumor’s spread.

-

References to “Billy Shears” and Sgt. Pepper packaging — source type: liner notes and press interpretation; verification test: read Sgt. Pepper packaging, early reviews, and the band’s contemporaneous public statements.

Why people cite it: The fictional “Billy Shears” from the Sgt. Pepper packaging and other on-album names were treated by believers as possible pseudonyms or clues pointing to a replacement. Histories indicate these interpretations were speculative readings of creative work; the band and press officers repeatedly dismissed the idea that those elements were part of any cover-up.

-

Sales spike and media coverage — source type: industry reports and news coverage; verification test: check trade reporting from late 1969 and contemporary newspapers.

Why people cite it: Record-company recollections and trade reporting show Beatles catalogue sales rose during the rumor’s peak; proponents argue that the behavior of record buyers and the intensity of coverage are circumstantial evidence of a deeper story. However, sales and press interest can be explained by curiosity and the market dynamics of sensational coverage rather than proof of the claim itself.

How these arguments change when checked

Many of the most-cited arguments weaken substantially when examined against primary sources or contemporaneous reporting. The single most important provenance point is that much of the modern clue list was synthesised, embellished, or invented during October 1969 radio and campus coverage rather than emerging from the Beatles’ camp as intentional signals. For instance, a satirical Michigan Daily item by Fred LaBour explicitly presented “evidence” as a parody, and LaBour later said he invented many of the alleged clues; that article was one of the pieces that national outlets then amplified.

Backward-audio claims are particularly sensitive to suggestion and expectation: audio that sounds like a phrase when someone expects to hear it can often be shown to be ambiguous or illusory under blind testing or expert transcription. Major retrospectives and reputable fact-checking note the role of pareidolia (hearing patterns in noise) and suggestibility in many of the audio-based claims.

Photographic details such as the Abbey Road license plate and Paul’s barefoot appearance are verifiable as real photographic features, but the interpretive leaps — symbolic numerology for age, immediate assignment of funeral roles to walk order, or strict forensic conclusions from casual photographs — are not supported by production notes or direct statements from the Beatles. Additionally, contemporaneous denials and interviews (including a widely circulated Life Magazine interview in November 1969) were used to counter the rumour at the time. That rebuttal did not stop interest immediately but is a documented part of the record.

Finally, authoritative fact-checkers and popular press histories classify the episode as an urban legend and hoax rather than a claim supported by robust primary evidence; they document how campus satire, radio discussion, and pattern-seeking combined to create the phenomenon. When checked against contemporaneous documents, public statements, and later investigative reporting, the separate elements mostly become ambiguous or are shown to have non-conspiratorial explanations.

Evidence score (and what it means)

- Evidence score (0–100): 12

- Drivers: the claim relies mainly on interpretive readings of artistic materials (album photos, lyrics, sounds) rather than independent primary documents or eyewitness testimony corroborating a death-and-replacement event.

- Drivers: several key “clues” were propagated or created during October 1969 campus and radio coverage, including a satirical college paper item that its author later said he invented.

- Drivers: contemporaneous denials and interviews (including press work in November 1969) are documented and reduced the rumor’s plausibility in mainstream reporting.

- Drivers: modern fact-checking and scholarly analysis characterize the story as an urban legend and highlight psychological mechanisms (pareidolia, confirmation bias) that explain why listeners read meaning into ambiguous material.

- Limitations: absence of certain types of disproof (for example, internal Beatles records explicitly cataloguing every photograph and lyric intention) leaves small interpretive gaps that fuel continued speculation.

Evidence score is not probability:

The score reflects how strong the documentation is, not how likely the claim is to be true.

This article is for informational and analytical purposes and does not constitute legal, medical, investment, or purchasing advice.

FAQ

What started the ‘Paul Is Dead’ (The Beatles) claim?

The modern, widely amplified rumor coalesced in October 1969 after a caller to Detroit DJ Russ Gibb mentioned alleged clues and encouraged reverse-play checks; a Michigan Daily satirical article soon catalogued “evidence,” and radio programs and newspapers amplified both the caller’s claims and the campus piece. Contemporary reporting and later histories identify those broadcasts and the Michigan Daily item as the main accelerants.

Did the Beatles or Paul McCartney ever confirm the claim?

No credible confirmation exists. The Beatles’ press office and the band’s members denied the rumor at the time, and Paul McCartney participated in high-profile interviews (including a Life magazine interview in November 1969) that were used publicly to rebut the story. Later public statements and media appearances by McCartney have treated the claim as a long-running hoax.

Are the “backmasked” phrases like “turn me on, dead man” real?

Backward-interpretation claims are documented as a major part of the 1969 discussions, but audio experts and historians caution that these perceptions are highly suggestible and often emerge only when listeners are told what to expect. Scholarly and journalistic treatments describe backmasking claims as ambiguous and prone to pareidolia.

Why do people still search for new clues about ‘Paul Is Dead’?

Because the original episode combined ambiguous artistic material (lyrics, photos), a media-amplified rumor, and a cultural moment in which conspiracy thinking was common; that blend makes the story especially durable. New analyses, re-examinations of photos, and occasional viral posts revive interest even decades later. Comprehensive histories note the phenomenon’s social and communicative qualities rather than treating it as a single evidentiary event.

How should someone evaluate a new “clue” they find?

Ask three questions: (1) Is the source primary (studio notes, dated production documents, contemporary interviews) or secondary/interpretive (fan sites, retrospective lists)? (2) Can the detail be independently verified in multiple reliable records? (3) Could cognitive biases (pattern-seeking, suggestion) explain the perceived pattern? If a purported clue depends on heavy interpretation or originated in later retellings, treat it cautiously.

Culture writer: pop-culture conspiracies, internet lore, and how communities form around claims.